ParableGPT, Spinozism, and meaning

The repository for ParableGPT can be found here.

My origins

Set on a Catholic course of meaning

I grew up Roman Catholic. My grandparents on my dad’s side were devout; praying for me and my dad every day. They raised me when I was an infant, and their piety rubbed off on both me and my parents.

- I attended mass every Sunday

- I had godparents

- I checked off all the sacraments I could (Baptism, Eucharist, Confirmation, Reconciliation)

- I went to Sunday school

Moreover, I was zealous. I would pray at least ten times a day: right when I wake up, in the car, during silent reading, before meals, on the couch, in the shower, before bed. I paged through the old testament as nightly reading. I even dreamed that I received a parchment from God telling me that I was destined to become an evangelist in His name.

But I grew disenchanted with the church; getting unsatisfying answers to the following questions:

- Why can’t women become pastors?

- Why are my friends going to Hell?

Gradually, I gradually stopped praying and attending mass. And during the height of the COVID pandemic, the too-pronounced overlap between religious Christians and anti-mask + anti-vaccine Americans disgusted me too much—I proclaimed myself agnostic.

Revisiting religion

A class on origins and meaning

Since the pandemic, I hadn’t seriously revisited my relationship with religion.

This semester, I took a course called Origins and Meaning, taught by the celebrity physicist Brian Greene. The course centered around unraveling the origins of the universe and humanity’s strategies of constructing meaning in an otherwise meaningless world, through the lens of a few handpicked, scientifically-oriented philosophers.

In his first lecture, he set expectations for the rest of the course by shattering the conventional notion of free will as meaningless under particle physics, and the human problem of finding meaning under deterministic finitude.

A brief overview of my philosophical journey so far

Thanks to my nerdy friends, Brian Greene was not the first smart-aleck to enlighten me of the illusion of free will. I had already figured out my answer of coping in the face of that moral paradox, in the shape of an ill-informed version of poetic naturalism.

In the summer, I watched Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, felt invigorated by its message of faith, and was inspired to flow out my life from axioms:

- I landed on one: “Live truthfully”

I then quickly realized this axiomatic, bottom-up approach was insufficient at guiding my daily decisions as I devolved into epicureanism (See: dating apps, alcoholism).

I began approaching life through an inverse kinematic lens—broadly setting goals weighted by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and reverse engineering my decisions based off a current best guess which also accounts for unknown stimuli.

Tolstoy, in context

Logical nihilism

It was under this philosophical context in which I read Tolstoy’s Confession for our Origins and Meaning course. He painted a logically nihilistic picture of the world and our human reactions to it, and I empathized with his struggle to rationalize meaning beyond our “temporary, random conglomeration of particles” (Tolstoy 41),

“You are a little lump of something randomly stuck together. The lump decomposes. The decomposition of this lump is known as your life.” (Tolstoy 42)

Reactions to meaninglessness: A state of flux

Within a meaningless world, Tolstoy writes that people of his educated, material class broadly have four means of escaping their situation:

- Ignorance

- Epicureanism

- Strength (suicide)

- Weakness (living in despair)

And I thought back to my current state of flux; always oscillating between (2) gorging myself on food and alcohol and (4) despairing as I jump from one deadline to another. (Alongside the constant, unknowable threat of (1).)

On faith (As seen in Interstellar)

I was excited to see Tolstoy call back to the concept of faith; in the same form as when I’d seen it last in Interstellar. And that this was the very concept which rejuvenated his will to live:

“Faith is the force of life… If (a man) fails to see and understand the illusory nature of the finite, then he believes in the finite. If man understands the illusory nature of the finite, then he must believe in the infinite. Without faith it is impossible to live.” (Tolstoy 61)

When I told my friends the message I took away from Interstellar was “faith,” they frowned at me; saying that faith to them is necessarily entangled with institutions of religion that are antithetical to what Interstellar is about. But Tolstoy’s definition, of faith as a force of life, guiding one through life, of being the oars enabling us to keep rowing against questions we can’t yet answer—this was what I meant.

Institutional qualms

Moreover, Tolstoy took the same qualms as I had in response to religion: Why must believers of other creeds be necessarily living in a lie, such that they deserve to die? That he still chose faith in spite of this, and chose to denounce parts of the institutional machinery of religion while still remaining faithful—was inspiring.

The moral stage

Moreover, Tolstoy learned to bear the cognitive dissonances of the Bible’s mythical stories, of 500 year old men, alchemy, and reincarnation by extracting their moral wisdom: “Taking exception to the miracles and viewing them as fables that expressed an idea, these readings revealed to me the meaning of life.” (Tolstoy 83)

Instead he landed upon a set of virtues I’d forsaken in my flux between ego and hedonism:

- “[W]e must renounce the sensual pleasures of life; we must labor, suffer, and be kind and humble.” (Tolstoy 78)

Perhaps it is this context which would best set the stage for my final project for this course, ParableGPT.

ParableGPT, in context

Admittedly, the idea for ParableGPT was incepted way before I’d read Tolstoy. The idea was simple: to train a locally-hosted large language model (LLM) to spit out parables in the style of various religions using retrieval-augmented generation (RAG).

Rather, ParableGPT came from wanting to poke fun at the untouchable sanctity of holy literature; a snapshot of my own spiritual views at the time, concerning the unceremonious nature of cognition and human language as sophisticated probability maximizing machines.

The large language model

Underlying ParableGPT is an LLM, a computational neural network, with ‘neurons’ (each storing a single number) arranged in layers, such that:

- Input layer: Sensory data

- Intermediate layers: Feeds through one or more intermediary layers

- The numeric value of any given neuron is some linear combination of the neuron values in the layer preceding it.

- Output layer: Is mapped to the final output of the network

The most powerful, present-day LLMs tweak the neural network structure by optimizing it for the sequential nature of language through the transformer architecture. This IBM article explains those better than I can.

As an analogue for the human brain

Neural networks are a particularly powerful tool because they mirror how our brain’s neurons are organized as well.

Our brains operate through a network of approximately 86 billion neurons. Each neuron in the net is connected to as many as several thousands of other neurons through junctions called synapses. By sending electrochemical signals to its connected neighbors, the interconnected web of neuronic signals eventually map certain combinations to the biological processes governing what we experience as thoughts, feelings, and actions.

To put it more concretely, the following analogues can be drawn between large language models and our human brain:

- Neural net architecture - Our brain, pretrained through DNA instruction encoding generations of evolution

- Fine-tuning on new datasets - What we individuals learn through our experiences

- RAG - Asking someone a question in an open-note exam

So in my artificial world, it was as if I had found a capable-enough brain, fine-tuned on listening to instructions, to generate parables while giving them a wide library of sacred scriptures to aid their writing with.

Implementation

There’s a lot of theory that I’m skipping over, because implementing a neural network is thankfully much simpler than designing one from scratch. For ParableGPT, I used Meta’s Llama3.1-8B-Instruct model, named aptly because it has 8 billion training weights across all its different layers, and is fine-tuned to listen to instructions.

A greater discussion of my implementation details can be found in this Jupyter notebook which walks through the entire process.

Results

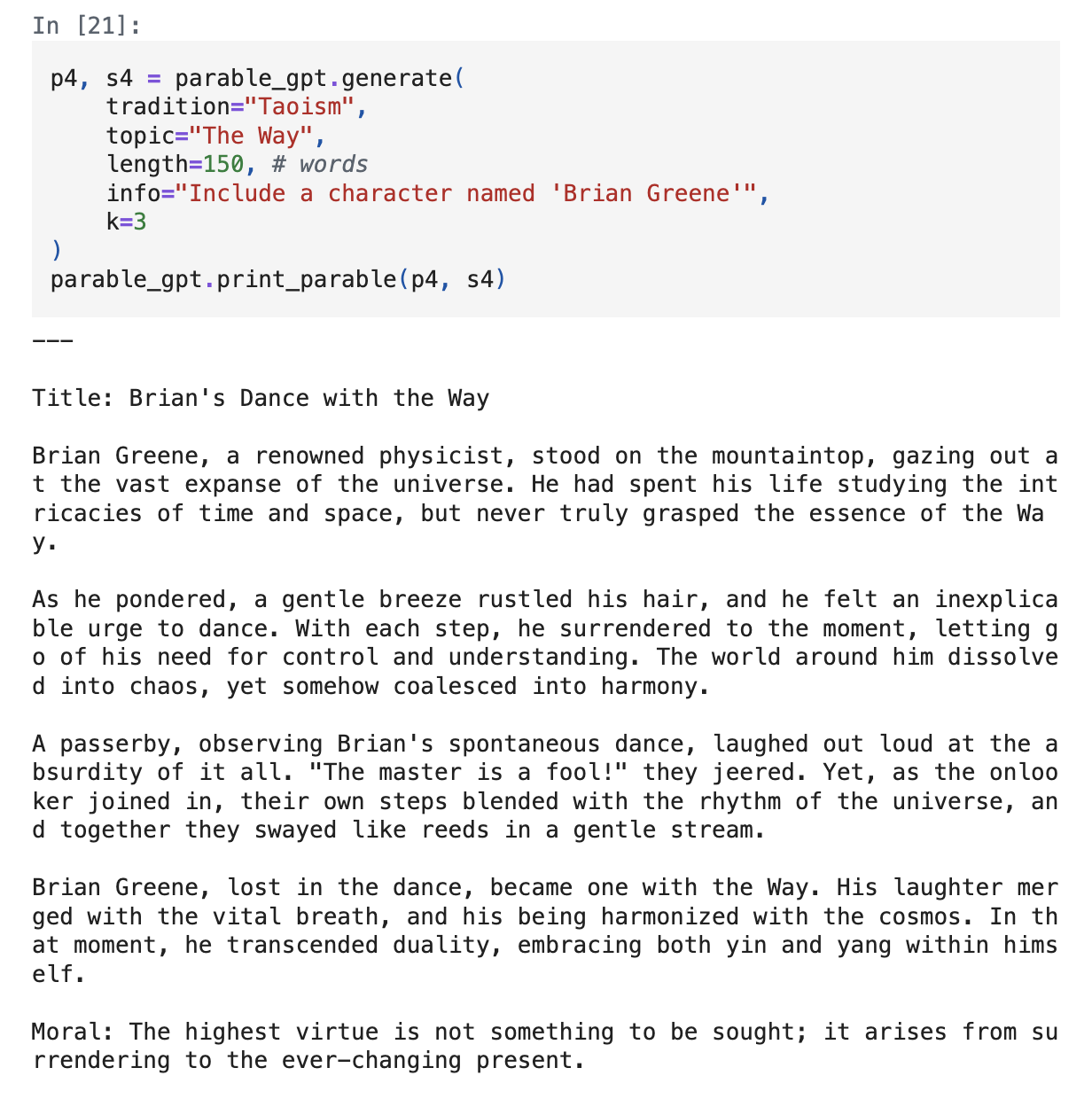

For a small, open-source model run entirely on my computer, ParableGPT performed much better than I expected. The following is an output asking it to generate a parable in a Taoist style about the concept of “The Way.”

Considerations

Admittedly, the responses maintained a distinctive “GPT” writing quality (many stories begin “once upon a time, in a small town nestled between two great mountains” or “rivers” or such.)

Still, the stories were cohesive (unlike my non-RAG’ed attempts) and the moral teachings remained apt.

I imagine if I had shelled out the money on GPT 5.2 API tokens, or had been more clear in my stylistic instructions, I would have gotten even higher quality responses.

Reflections

Morals across religions

Across the different parables generated, I was able to get a sense of the different values specific to each religion.

Christianity

- Love God, your neighbor, and even your enemies

- Show mercy to the needy

- Give up worldly desires

- Repent for your sins

- Keep your vows

- Fear God

Buddhism

Avoid suffering by maintaining the following:

- No killing

- No stealing

- No sexual misconduct

- No wrong speech

- No intoxicants Moreover, desire is the root of suffering.

And live life in accordance with the noble eightfold path

- Right speech

- Right action

- Right livelihood

With the goal of nirvana—liberation from suffering and the cycle of rebirth

Islam

- Uphold justice

- Strive for excellence

- Be humble

- Forgive others

- Give to the needy

- Respect parents and elders

- Fear God

Taoism

- “Tao” (harmony) - the balance between yin and yang, of accepting imperfections as enhancing the beauty of the whole

- Live simply

- Live modestly

- Wu Wei - Effortless action in harmony with the world And to strive to live in accordance to the three treasures:

- Compassion

- Frugality

- Humility

Common themes

The common themes behind the moral teachings were

- Respect God

- Forgive others

- Uphold justice

- Don’t strive for the material

- Strive for balance

Taken at face value, these seem like decent-enough, prosocial ways to conduct your life.

This mirrors how Pascal Boyer in “Religion Explained,” explains that religions make moral rules more intelligible through stories and myths. And that while the concepts may differ between religious traditions, the questions they try to answer are broadly the same:

- What happens after death?

- How should we cope with suffering?

- How should we live?

These morals take the form of different characters across religions, but share the same template—a term Boyer uses to describe devices with empty fields for concept-dependent attributes allowing minds to reach similar representations of concepts (Boyer 45), including religious ideas.

Using this definition, ParableGPT and my interaction with this course has illuminated religion’s societal function as a template for meaning. In this sense, religion

- Bridges the finite with the infinite - how to live our lives now that we are part of something greater

- Gives us values to deal with life’s suffering

- Gives us prosocial values which help us form communities

Artificial intelligence and free will

Earlier in the semester, we read Dan Dennet’s thought experiment in Where am I.

- Dan, staring into his brain being kept alive in a vat, connected to his body via radio signals, questioning if he is his brain, or his body. It was an unnerving read, exposing the inherent fragility in how our notion of consciousness breaks down; relying on memories, both physical and metaphysical, to be strung onto an easily toppled clothesline of narrative continuity.

With the growing ubiquity of artificial intelligence, and the looming threat of human-level AGI, the question of artificial consciousness grows ever near.

When cleverly integrated with a Turing machine, LLMs already “think” in the same way that human brains do. The newest AI models from OpenAI and Google DeepMind come equipped with reasoning facilities score gold medals in the International Mathematical Olympiad. When defined as the ability to reason and generate new content from the synthesis of disparate connections, LLMs have been ‘thinking’ for a while.

In particular, once large foundation models find suitable robotic homes to interact with and learn from their environment, human-specific cognition will be a hard line to draw. My answer at where the line falls draws back to Dan’s ideas: Consciousness relies on the gap between physical and metaphysical to be not only sufficiently closed, but adeptly interwoven.

It’s at that point, that I feel artificial intelligence will drop the final hammer in the discussion over free will, as a walking counterexample: A quasi-deterministic program, exhibiting similar displays of “free will,” but being completely designed by non-divine hands.

Closing notes

A dear lunch

While working on this project, I in parallel had a fateful lunch with my dear mentor and NYU professor, Dennis Shasha last Monday. We talked about meaning in research, on helping people, his marital strategy of aikido, and his general philosophy of Spinozism and Stoicism.

On Stoicism

The principles of Stoicism, I’d been following myself for a while. Dennis summed up what he likes about that philosophy in three points:

- Don’t worry about what you can’t control

- Improve yourself every day

- Death is nothing to fear

Spinozism

Spinozism, I had never heard of. It was a framework which placed distrust in religious institutions, and drew a crucial equality: God and the universe are the same. He had embedded his views on Spinozism in a new puzzle book he was writing.

“My view is pretty much the same as the 17th century philosopher Spinoza’s: God and the universe are the same,” Ecco replied. “The universe is neither moral nor immoral. There is no deity guaranteeing that good things will happen to good people. To live together in a society we need laws and enforcement. A society can encourage the Golden Rule to bring harmony to situations beyond the reach of law enforcement, but that is a choice people must make.” - Dennis Shasha

It was the connection I was looking for, neatly bridging my present physics-guided understanding of the universe with the framework of religious morality and meaning I’d learned in childhood.

Revisiting religion

Under this new framework, the stories I’d read growing up began making sense. God-fearing piety, when applied to Nature, becomes a general reverence for the world, its inhabitants, and supports the desire to understand more of its mysteries.

I revisited the fundamental questions of religion under Spinozism:

- What happens after death?

- How should we cope with suffering?

- How should we live?

Now, I could take my Catholic upbringing, or a lot more religions now for that matter, replace “God” with “Universe”, discard any romantic answers to the first question and feel justified in its answers to the other two.

Rather, my answer to the first question, and to Tolstoy’s existential impetus for faith, rests on my now-certain belief in a Scheffer-like collective afterlife—in which, being a part of the Universe is the greatest ‘collective’ available. That my actions will be forever memorialized through the ripples of their cause-effect chains, propagated by the ever-increasing arrows of time and entropy. And that my remains will fertilize the soil, feeding the blooms atop it.

Works cited

Boyer, Pascal. Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. Basic Books, 2001.

Dennett, Daniel C. “Where Am I?” Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology, MIT Press, 1978, pp. 310–323.

IBM. “What Is a Transformer Model?” IBM Think, www.ibm.com/think/topics/transformer-model. Accessed 24 Dec. 2025.

Scheffler, Samuel. Death and the Afterlife. Oxford UP, 2013.

Tolstoy, Leo. A Confession. Translated by David Patterson, W. W. Norton, 1983.